July 4, 1914 – Glorious Day Ends in Tragedy

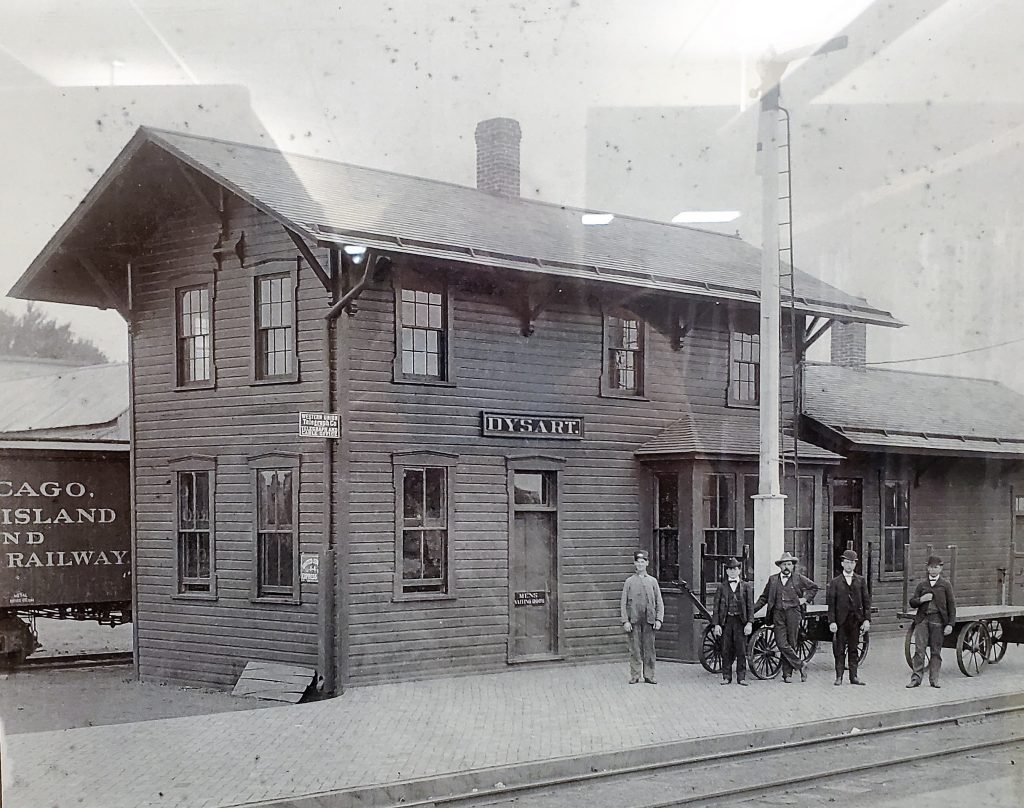

Dysart Train Depot

It is after 11 p.m. and the platform of the Dysart train station is crowded with people and packages all waiting for the #420 Rock Island train which will take them east. Most are headed to the town of Vinton. With a population of about 3,300 people, Vinton is three times larger than Dysart. No Fourth of July celebration was offered there, so Vinton residents came here earlier today to enjoy the excitement of Dysart’s celebration. That train was late too.

Most are not disappointed with their decision. They have had a fun and exciting day full of interesting sights and sounds and smells. They have been entertained by Vaudeville acts performed live and for free. They have played games of chance, and some hold a souvenir of their victory. Their beloved baseball team, the Vinton Cinders with the popular Lynch and Miller brothers have emerged victorious from the two games they played today. Some of the young people met someone at the dance who they are now thinking about and hoping they will see again.

It has been a glorious day-long break from the work that normally consumes their lives but now they are growing tired and maybe a little antsy. There are no benches at the train depot, and everyone waits outside in the night air. They jockey for space where they can. No one wants to be the last to board. Standing in a moving train for fifteen miles seems like a bit too much after the day they have had.

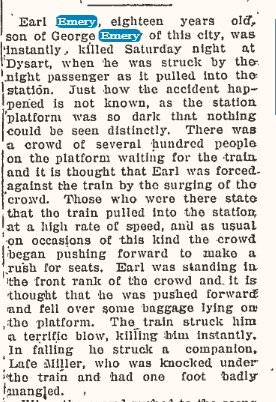

Earl Emery

Among those standing on the platform are two young men from the Vinton area, Earl Emery, and his friend Lafe Miller. Earl is just seventeen, but he has seen a lot of life already. Three years ago, he stole $75.00 from his father and left alone on a train for Alliance, Nebraska, where his mother is buried. Apprehended, he was sent to the reform school for boys in Iowa and has been recently released. He now lives near his dad who got him a job at the S. Robinson Company where he worked in the manure spreader department. Within the past few weeks, he traded that position for one as farm hand. After a rocky adolescence, he appears to be headed in the right direction. His friend, Lafe, is originally from Indiana but came to the Vinton area two years ago to work as a farm hand on the Oxtel Bostrom Farm.

The headlight of the railroad locomotive appears to the west and the crowd starts collecting their things in anticipation of going home. What happens when the train reaches the platform will be disputed, misreported, and sensationalized to sell newspapers in the days ahead. But the result will be the same. In a few short minutes, Earl Emery will be dead, and Lafe Miller will be maimed for the remainder of his life.

The Aftermath

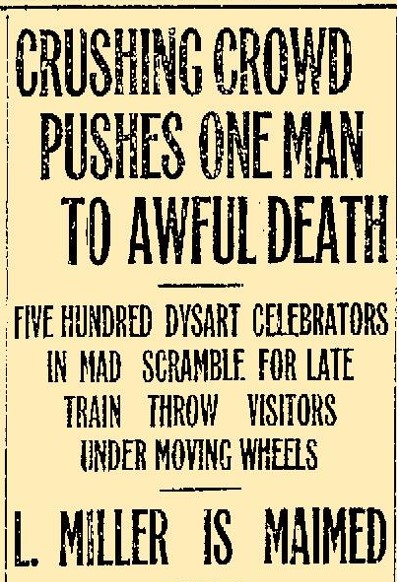

The local paper, The Dysart Reporter, was a weekly publication, so they were not able to report the incident until five days later. However, starting on July 6 several other papers around the state picked up the story and started to report their versions of what happened. One of the first papers to break the story was the Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette which immediately sensationalized the tragedy. On July 6, 1914, their headline read:

Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette

That same day, the Des Moines Register in a brief article reported that eleven deaths were reported across the state on the 4th. It reads “Sunday’s toll of deaths from accidental causes was sixteen, eleven being the result of automobile accidents, four were drowned and one Iowan being killed by a train when shoved off the station platform in Dysart, Iowa. The Waterloo Courier also placed the blame an unruly and selfish crowd. The Evening Times Republican out of Marshalltown proposed the cause of the accident was Earl and Lafe’s position on the platform not the crowd.

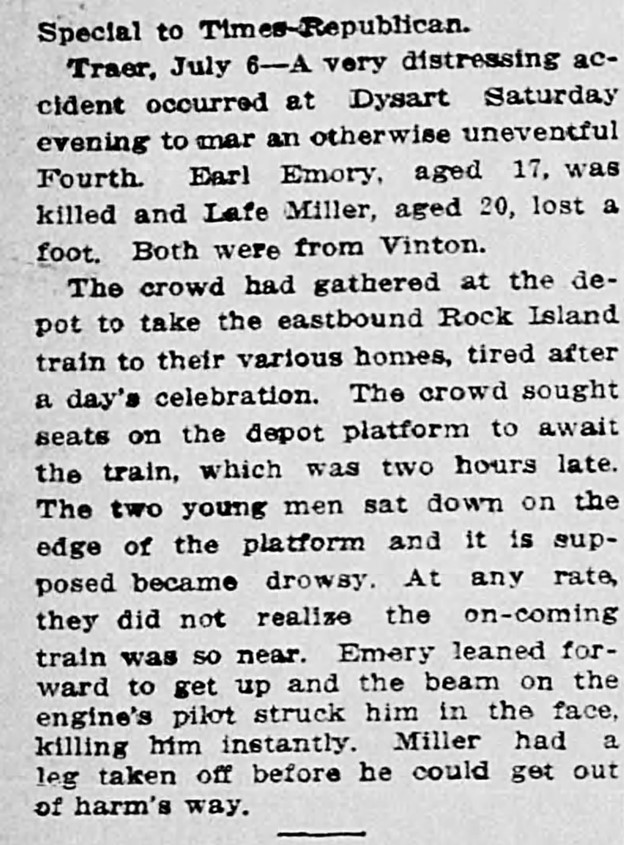

Evening Times Republican

In truth, Lafe Miller did not lose a leg. On July 7th the boy’s hometown paper, the Vinton Eagle proposed yet another explanation of what happened on the platform that night. Because most of the people were from Vinton, it might be assumed this version is more accurate as the editor likely interviewed witnesses who experienced what happened. Speaking of Earl, they wrote:

Vinton Eagle

They reported Lafe’s injuries in more graphic detail but also noted that a woman had most of her clothes torn off by the suction of the train. This detail is not repeated in any other paper that could be found.

Vinton Eagle

The Cedar Rapids Republican’s coverage combines the hypothesis that because of the crowded conditions, Earl was standing too close to the train when it entered the station and was struck by some protruding part. It does also note that “he was hurled many feet into the air alighting beside the platform.”

The local paper, the Dysart Reporter, carried the story on July 9, 1914. Their tone is less sensational and more factual. In their version, Earl and Lafe were killed and injured by a train, not by the people waiting for the train.

Dysart Reporter

In whatever way the accident occurred, one can only imagine the horror and shock the boy’s fellow passengers and friends experienced that night. Surprisingly, the extensive reporting that followed in all the papers has a lack of eyewitness accounts. The Reporter went on to speculate the details as follows:

Dysart Reporter

Crowd Accused of Murder

The Waterloo Courier on July 9 took everything up a notch by accusing the crowd of murder in the death of young Earl.

Waterloo Courier

The story continued to be reported across the state for a few days after July 9 on which date the Vinton Review published this account which seems like the most likely explanation. It combines the notion that the crowd was pushing and that the boys were too close to the tracks. It also reiterates that although hundreds of people were present, very little could be seen on that dark night when outdoor lighting was just starting to be installed in towns across Iowa.

Vinton Review

The Traer Star Clipper concluded their coverage in this way:

Traer Star Clipper

Later in the month, the editor of the Keokuk Daily Gate used the Courier’s indictment of murder as the basis for an editorial on the selfishness of man and unruly crowds.

All the papers were able to agree that Earl lived for a brief few seconds after being hit but the train because witnesses heard his rattled breathing. They were also able to agree that Lafe was horribly injured and in need of medical attention. We know that one of the towns’ doctors, F.W. Gessner, was called to attend to his injuries because he would later testify to the same. In the hopes of saving his foot, Lafe was loaded on to that same train and taken to Cedar Rapids’ St. Luke’s Hospital. He was hospitalized for several weeks but the foot was saved.

These events happened on a Saturday. Earl’s body was taken to the Kranbuehl undertaker’s parlor. The following Monday, his father arrived in town and took Earl’s body to Vinton. A funeral service was held at the Presbyterian Church, and he was interred somewhere near Vinton although where is not clear.

Starting in September, a few different lawsuits were filed against the Rock Island Railroad and the engineer, George Godden. George McElroy, administrator for Earl’s estate and Earl’s father both filed suits which were settled in December for a total of $1,250.00. J.W.Agers who was listed as guardian for Lafe also filed a suit asking for $7,500. A settlement may have been reached but that information is lost to time.

Lizzie Emery 1877-1908

Earl Martin Emery was born in Clinton, Iowa, on Valentine’s Day in 1896 to George and Lizzie Emery. His mother, Lizzie Marie Clark Emery died, at the age of 31 on January 13, 1908, when Earl was just twelve years old. After her death, his father, George, moved the family to the Vinton area. He was remarried in 1909 and apparently divorced the following year which is the year that Earl took off for Nebraska. He was married a third time to Myrtle Mae Fisher. George died in 1952 and is buried in the Evergreen Cemetery in Vinton. Update 7/15/2025: Susan Jessen of Clinton Iowa, shared that Earl's unauthorized trip to Alliance was spurred by the fact that George had left Lizzie's grave unmarked, something that Earl wanted rectified. In 2023, Susan reports that she worked with the residents of Alliance to find Lizzie's grave and had a marker installed in her memory. Susan is the daughter of Earl's sister, Ruth E. Emery).

William Lafe Miller was originally from Bristow, Indiana, and had been working in Vinton over the summer along with his two brothers. Lafe became a mechanic and either owned or worked at shops in Garrison, Dysart and Clutier. In 1928, he and Olin Smith purchased a garage business from John Helm in Dysart. He became the sole owner of that business in 1930. He and his family (wife Marie Peterson Miller) lived on the main street. During the 1930s he drove cars out to California and sometimes advertised that he would take riders with him. By 1940, he and his family moved to the Phoenix, Arizona, area although he returned to Iowa several times over the years. He was living in Arizona in 1950 when the census taker came but his location after that is unknown at this time. Lafe appears to have either been unlucky or lucky sort of guy depending on your perspective. In 1916 he was involved in an auto accident and in 1922 he was injured when a battery exploded in his eyes.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing on our home page. You will get notices as new articles are published!