In 2023 the small community of Dysart, Iowa, celebrated their sesquicentennial based on the date that the town was established and named for a founding pioneer, Joseph Dysart. Becoming a named town helped the community establish itself. Of course, it was not the first step in the process of transforming this part of the midwest from the home of the native tribes to a settler’s town and thus changing the landscape of Iowa forever. Sources, including the Dysart Sesquicentennial publication and others, inform us that Tama County in which Dysart is located was established by the legislature in 1848 and that soon after settlers began to move into the county. In 1850, the population in the county was less than 20 white settlers. By 1853 the process of establishing townships was begun and growth continued. Between the years of 1850 and 1870 the population continued to grow steadily. After the Civil War, interest in railroads provided the structure and resources which led to a town being laid out and the building of an infrastructure which is the present day town of Dysart.

One of the first priorities of settlers was to establish ways to communicate with others for the purposes of social interaction and commerce. According to records, the first post office was located in Monroe township in Benton County and was named in honor of Squire James Wood. This served the surrounding area until 1863 when it was disbanded. Starting in 1864 all the mail was held in Vinton and settlers were required to travel to that location to collect their mail or have someone bring it to them when they traveled to Vinton.

And Then There Was Ettie, Iowa

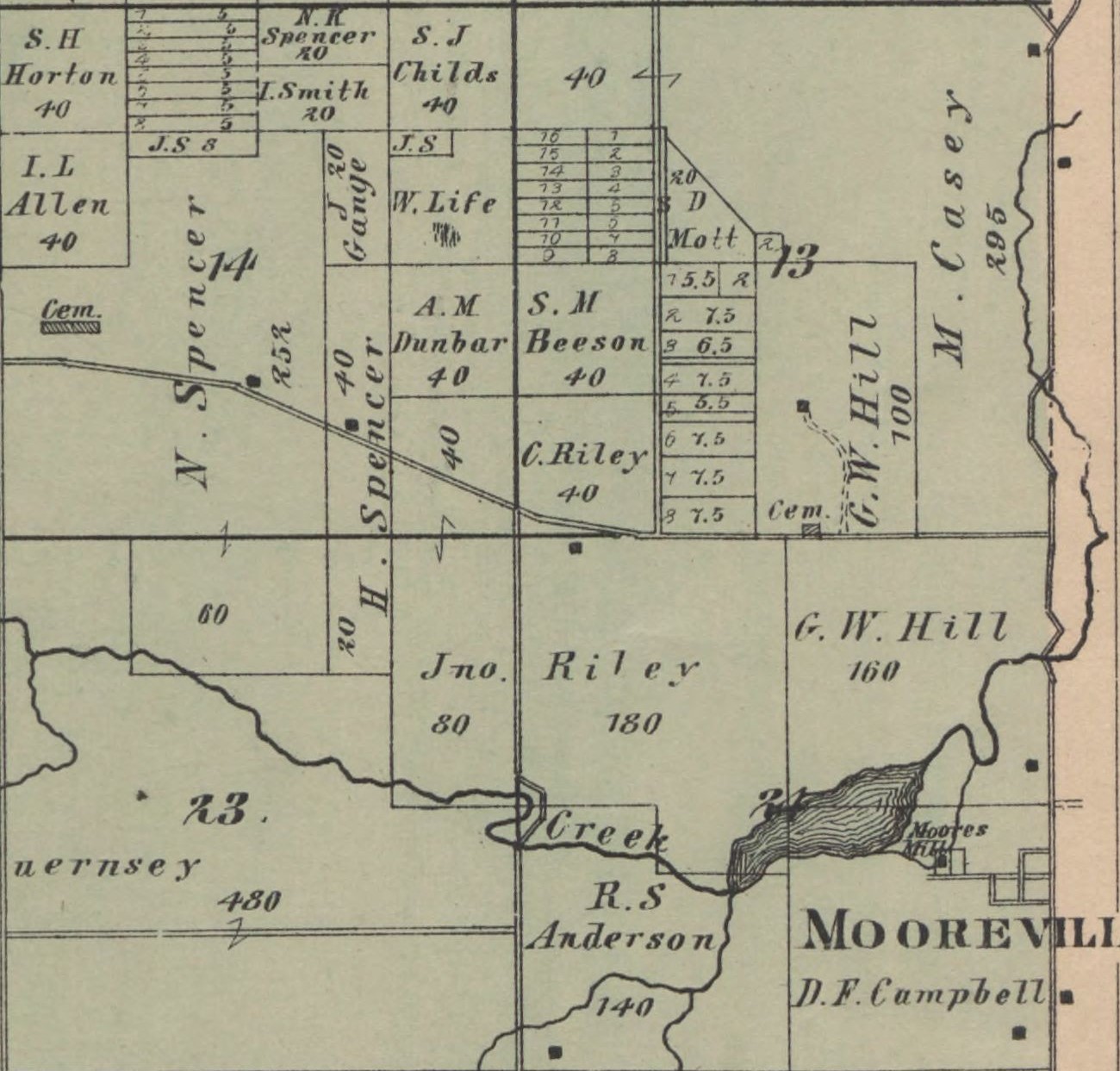

Finally, in 1869, a post office was established at the home of John Tyler Converse in section 11 where it remained until it was moved into the newly established town of Dysart on January 3, 1873. This post office was called “Ettie” and was primarily operated by John’s wife. Marcia. According to the obituary of their son, Palmer, “the family came to Iowa and located in Tama county, near Dysart in 1867. They lived there for thirty-six years. Mr. and Mrs. Converse disposed of their property at and near Dysart and came to Estherville in 1903.” The were eventually buried in the Dysart Cemetery. The Ettie Post Office was located on their farm. Today, if you drive north out of Dysart on the road which lies on the west end of the town and turn west, this farm is the first one on the right side of the road. Long-time Dysart citizens will recognize this location as the Seebach farm. Why the post office was named Ettie is not clear.

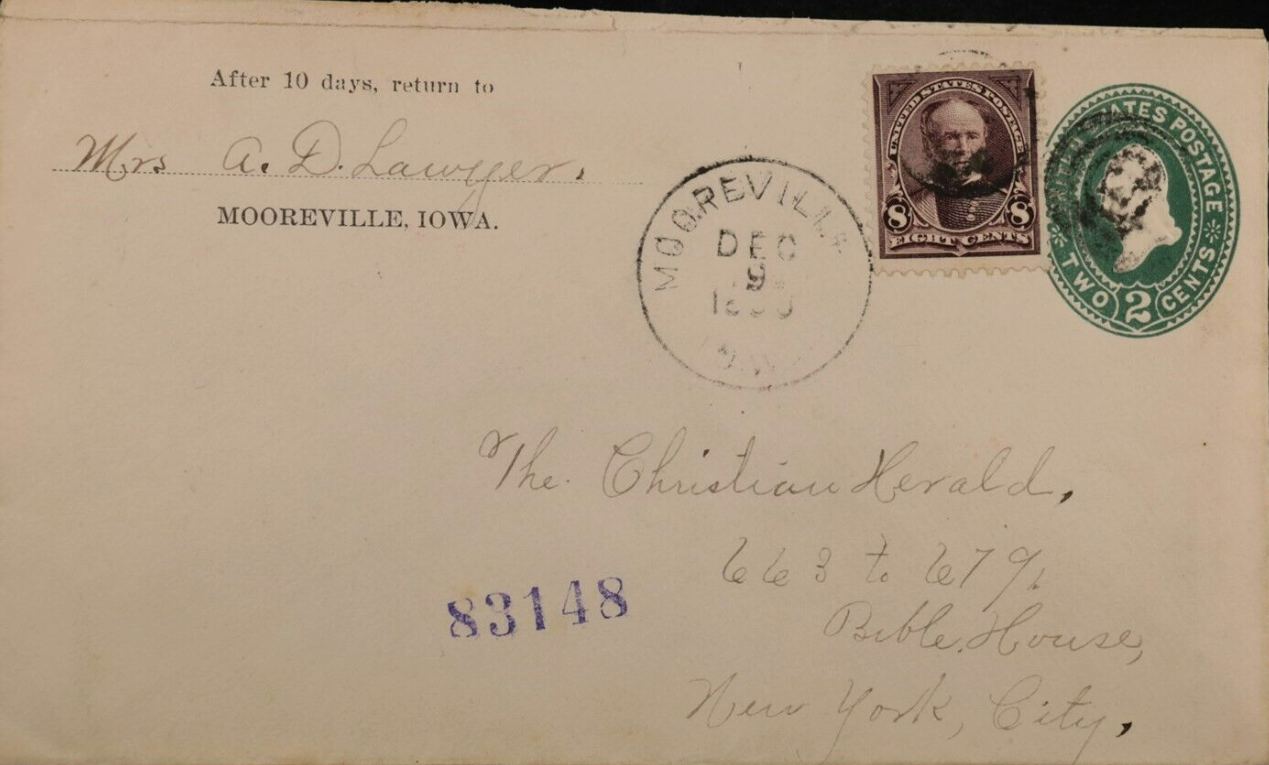

John Converse Original Application for Post Office to be called Ettie with move to Dysart noted

The New Post Office Is Announced

Thus, the area in and around Dysart was known as Ettie for about 4 years before the town was established. In those early days mail routes were bid on by local residents who were paid to run the routes. On March 10, 1870, the Post Office Department put out a bid for Route 11211 which ran from Belle Plaine to Waterloo twice a week and included stops at the Ettie Post Office.

Waterloo Courier March 10, 1870

In Iowa newspapers between 1869 and 1873 the name of Ettie was a location in stories, announcements and letters to the editor including this one from December of 1870.

The Toledo Chronicle December 15, 1870

As stated, the post office was moved in 1873 and the name was changed to Dysart where it has remains to this day. After the office was moved to Dysart, the name Ettie pretty much disappeared from the records.

Document from the National Archives showing change from Ettie to Dysart Post Office 1873.

Happy Zip Code Day to the Residents of Dysart! 5-22-24!